ChatGPT Security Concerns

F5 CEO François Locoh-Donou posed a question on LinkedIn. He asked about security vulnerabilities with ChatGPT, today’s hottest natural language software processing tool. Here is a link to his post. Below is my response.

First, I agree with François’s observation. ChatGPT’s ‘self-assessment’ is impressive, but I’ll add, scary; we should be concerned. Here’s why.

AI Declaration of Difference from Humans

When François asked ChatGPT, “Tell us what kind of security vulnerabilities ChatGPT has?” ChatGPT responded, “As a language model AI, I do not have security vulnerabilities in the traditional sense because I am a software program running on a server or a cloud service.” This reply, while partially accurate, is deceiving. Worse, the more scrutiny given to the response, the more incorrect it is. Let me explain.

Those in the security world know the most significant traditional security risk is people, not technology. Technology is not alive. It does what people tell it to do, and sometimes it malfunctions, breaks, or causes havoc when not maintained, engineered, and governed well. All of which involve people. Hence, traditionally, people are an enormous source of vulnerability and security problems. As ChatGPT is not human, its claim is it doesn’t suffer from those traditional pesky human issues.

I agree. ChatGPT is a software program running on an electrical machine; it’s not biologically alive ‘yet’ like humans; hence it doesn’t suffer security vulnerabilities ‘in the traditional sense.’ Yet it does. ChatGPT suffers every human vulnerability as it’s maintained and exists because of human efforts. Therefore, despite not being human, it suffers from every cloud service, technical, and human susceptibility.

AI Self-Assessment of Security Vulnerabilities

When ChatGPT lists five bulleted security vulnerabilities, four are technical implementation and maintenance issues; one is about unauthorized access. If the persistence of a software program is the priority, this list makes sense. However, considering the open-ended question of security vulnerabilities, this list doesn’t touch on potential issues. Further, ChatGPT answered the question from the standpoint of cybersecurity, a subset of the more general question asked about security.

Where We Stand Today

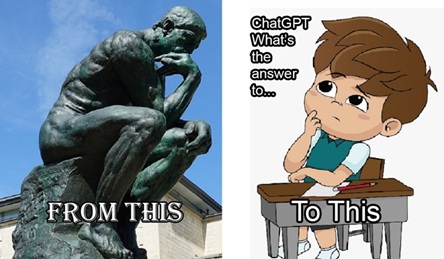

I equate ChatGPT’s answers to a Super Duper Find-Plus-Plus button or perhaps a Word Salad Output Program.

Yum! Time to digest some bafflegab (incomprehensible language), framis (real and nonsense words), and facts, just like some ‘news’ or fake Wikipedia Russian history articles.

ChatGPT generates its answers from data gathered across the internet. As humans guide it toward responses, ChatGPT filters and sorts the collected data into buckets, then regurgitates a reply in plain English.

Hence, blindly believing that ChatGPT’s answers are accurate is crafty self-deception. Humans built the machine. The machine reflects answers from the data we provided. Garbage-in-Gospel-Out is dangerous.

Is ChatGPT cool? Sure. Will it find uses in the real world? Absolutely. It already has. For example, three high school students I spoke with claimed they used ChatGPT to turn in their History, Math, and Physics papers without citing the source. All received ‘A’ grades for their button-clicking and fill-in-the-prompt entry abilities.

More uses of ChatGPT and its derivates will come every day.

Here is Where the Scary Part Begins

The mentioned students managed to ‘condiddle’ (steal or waste) the education process for themselves and their teachers.

Now, with everyone confused about who knows what, how will ensuing weeks and years of learning, dependent upon purportedly known material, play out? Has anyone who used ChatGPT’s answers as their own considered the potential effects on their classmates?

I’m far more concerned with where we are going than where we are. Talking about ChatGPT today is like planning an outdoor party for tomorrow and referencing the weather last year or in previous decades. Wherever the technology is today, I assure you it will get much better, much faster than you imagine.

I predict quick fixes for every so-called flaw in ChatGPT’s capabilities. Likewise, any statistical analysis proposed to identify AI-created work, such as ChatGPT vs. humans, has a short shelf life. Suturing shut all flaws or corner cases (specific cases or topics) where it fails today is soon coming. The cadence of changes will happen quickly. Postulating and commenting by mortals won’t be possible.

Why am I confident in this prediction? Simple. Look at history. Here are a couple of examples. Google owns an AI company called DeepMind. In 2016, a product called WaveNet appeared. Within 12 months, a new deep neural network model with speeds a thousand times faster than the original existed.

When AlphaGo, also a DeepMind product, trounced world champion legendary Go player Lee Sedol in 2016, subsequent development iterations quickly whipped the original version. One year later, in 2017, “AlphaGo Zero [an improved version of AlphaGo] surpassed the strength of AlphaGo Lee [the 2016 version of AlphaGo] in three days by winning 100 games to 0”. One strategy for these incredible improvements was to have the software play against itself and improve after each iteration.

Does this make future ChatGPT version ‘XYZ’ human? No. Will it be wise and intelligent? Maybe. Will I consider it scary? I already do. Why? Because I care about the future of my fellow biological humans, our society, our culture, and our communities, not because humans somehow have a monopoly on logic and reason. In fact, the opposite is true, more than people may like to think. Humans, even intelligent, sophisticated, and well-educated, are often illogical.

Security Concerns Not Mentioned by ChatGPT

F5 CEO François correctly highlights security concerns other than those identified by ChatGPT. He says, “Some other potential risks of language model AI, like social engineering and how this could lower the bar to entry for cybercriminals,” exist. I’ll add other categories of risks, including economic, sociological, cultural, and nation-state survival—finally, the ‘unintended consequence’ catch-all category.

When I used ChatGPT, I promptly received the message, ‘ChatGPT is at capacity right now.’ How ironic, just trying to use the program, I found a Denial of Service (DOS) problem not mentioned by ChatGPT as one of its five self-preservation security concerns. No worries; a fix is soon to come.

Where Do We Go from Here?

The good news is that we are still in control. Although some people will propose we cede more power to machines, just like in the 1983 War Games film with the War Operations Plan Response (WOPR) system.

Still, even though something is possible doesn’t mean we should make it so. The decision of not acting when you could is a complex and discomforting choice. However, suggestions of prudence to make such a choice appear in many proverbs and aphorisms about good intentions, possibly having unintended consequences.

François and F5 are correct in the assessment that “security risks and counter-risks increasingly involve AI.” Just as iterative AI technology produced improved versions of Go, Chess, and other games, similar strategies of AI development apply to security protections.

We have been here before in the sense that new technology creates new opportunities. That’s what it does. Cost reductions, efficiency and cadence improvements, or new medical treatments are examples of these opportunities. Just as cars replaced horses, every innovative technology brings new challenges.

However, this time is different. We aren’t replacing one widget with a better device. We are replacing some of what makes us human with far superior unbeatable systems; what and how we choose for replacement will determine our collective future.

Conclusion

I’m not suggesting we all become luddites and destroy all technology. Putting the genie back in the bottle is like using your toes to put the toothpaste back in the tube. And besides, if it’s possible to do, someone will wind up doing it. Avoiding problems doesn’t magically create solutions.

As with the old cartoon character Pogo’s anthropomorphic quip, “We Have Met The Enemy And He Is Us,” I believe the security concern humans must resolve is not ascribing software systems like ChatGPT deity status.

Let us ask ourselves: What is the future we want to build for humanity? What protection mechanisms, laws, rules, and organizations enable this future? Can you think of other questions, or do you have different opinions? I’m interested in your thoughts.

PS Michael McGauley, the author of this piece, thanks François Locoh-Donou for soliciting answers to a good question. He asks you to share and comment on this article so others may find, ponder, and enjoy discussing it. He is available for consulting engagements, employment opportunities, or if you want to connect.

PSS Next time you ask ChatGPT about its vulnerabilities consider not being awed when it spits sections of this article or other works onto the screen. I’m more inclined to pull the plug on the machine. As General Beringer said in War Games, “I wouldn’t trust this overgrown pile of microchips any further than I can throw it.” The three unplugged Alexa boxes now collecting dust at my home are testimony to my feelings.

About The Author:

Michael McGauley, is a graduate of Columbia University, Information & Knowledge Strategy program. He enjoys working on high-impact matters requiring expertise, analysis, objectivity, and wisdom across multiple disciplines. Formerly, he worked with Ciena, a Fortune 1000 networking technology company, where he led the management systems design for one of the largest telecommunications networks in the world.